On Saturday 19th of January, Nick Logan and I braved the

snow and caught the train to Marylebone Station. Hyper-cynical as I can often

be about art fairs, I was actually feeling quite excited about visiting this

year’s London Art

Fair.

|

| ©National portrait gallery / handout / Reuters |

Before making our way through the ice-cold sleet to buzzing

and grungy Islington, we stopped off at the National

Portrait Gallery, where Paul Elmsley’s

‘controversial’ painting of Kate Middleton is currently on show. Labelled as

“bland and predictable” by David Lee and “a rotten portrait” by Robbin Simon, I thought it was well-executed, but a rather stark,

hyper-realist portrayal; a little too ordinary for my tastes. And,

certainly, given the opportunity, this would not have been my own choice for a “first

official portrait”. One of the invigilators explained that the painting had been moved, as the

constant barrage of visitors, eager to get a peek at the Duchess’s

immortalisation, were blocking the hall way.

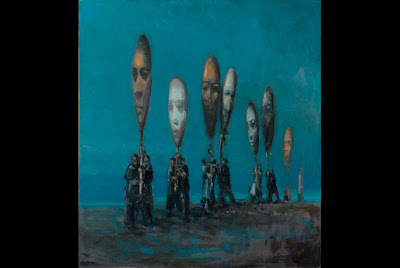

On the other side of the room, however, staring right

back at HRH, there was something that appealed to me a lot more: a series of

minimal, beautifully executed studies of Akram Khan, by the American-Iranian artist Darvish

Fakhr. The nine oil panels, which were taken from stills of the dancer in

motion, are inspired by the Khatak dance principle of the nine rasa,

traditionally expressed by a dancer through bodily and facial movements.

In another exhibition there was a painting of Nobel Prize winning scientist, Sir Paul Nurse (former Chief Executive of Cancer Research UK, famous for his important discoveries on how cancer cells divide), skilfully painted by acclaimed British artist Jason Brooks. “The largest realist painting that the National Portrait Gallery has acquired”, the work – commissioned by the Trustees and made possible with support of J.P. Morgan through the Fund for New Commissions – was developed over a series of meetings between the artist and sitter in New York and London.

In another exhibition there was a painting of Nobel Prize winning scientist, Sir Paul Nurse (former Chief Executive of Cancer Research UK, famous for his important discoveries on how cancer cells divide), skilfully painted by acclaimed British artist Jason Brooks. “The largest realist painting that the National Portrait Gallery has acquired”, the work – commissioned by the Trustees and made possible with support of J.P. Morgan through the Fund for New Commissions – was developed over a series of meetings between the artist and sitter in New York and London.

|

| Detail from the portrait of Akram Khan by Darvish Fakhr (Picture: The Guardian) |

Unfortunately,

the photograph doesn’t really do the painting justice, as you need to see the

incredible details up close, but this large, black and white ‘snapshot’ is meticulously

air-brushed, showing every pore, bristle and wrinkle. “I didn't want it to

reference science overtly,' explains the artist “but it does explore genealogy,

the make-up of the human form.” From a distance the image is sharply defined, photographic,

but it is actually composed of abstracted forms; an attempt, in the words of

the artist, to “get lost in somebody's structure”. “What's really important to

me,” says Brooks “is having that pornographic gaze, that forensic detail. The

flaws, the marks - they're the things that I fall in love with.”

|

| Sir Paul Nurse by Jason Brooks. Acrylic on linen (2008) © National Portrait Gallery, London |

Paintings

of ‘Sirs’ abounded with ‘Sir John Tavener’ by Michael Taylor and ‘Sir John Evans’, by

award winning painter David Cobley,

among others.

As we were swept from one time warp to another, it was interesting to be reminded of how, unlike today’s ‘superstars’, the artist was once merely considered a lowly ‘craftsman’. Browse through the earlier centuries, and most of the labels read: ‘artist unknown’. Then, suddenly, it is as if an artist’s rebellion has begun and ‘audacious’ self-portraits begin to crop up here and there, sometimes hiding among the brushstrokes of a royal or papal commission, rapidly followed by artists commissioning their own portraits from fellow colleagues.

For

the nostalgics among us, the absence of a name is very sad, but it also creates numerous problems for future observers, as has occurred with ‘The Somerset

House Conference 1604’ – again, here, the digital image does not do this

large-scale painting justice -, probably of Flemish origin, which allegedly

bears the false signature of Juan Pantoja de la Cruz. But, I don’t suppose you could blame him for wanting to

be associated with such a fine and fascinating painting...

|

| The Somerset House Conference 1604 © National Portrait Gallery, London |

|

| Augustus Edwin John by William Orpen (1900). © National Portrait Gallery, London |

There

were too many gems to mention, but among the many traditional portraits, I

particularly liked this moody yet impish depiction of Welsh artist Augustus

Edwin John (4 January 1878 – 31 October 1961),

by William

Orpen.

Another

painting that absolutely fascinated me was ‘Private View of the Old Masters

Exhibition, Royal Academy, 1888’ by Henry

Jamyn Brooks, an incredible snapshot of the openings of the times.

Leaping

back to the future, is the ‘Artists and Sitters’ section, with a series of

works spanning 1960-90. There was a painting of critically acclaimed poet Ted Hughes, by Barrie Cook, which made me

smile, as many years ago the poor man was given what was probably the painful

task of reading my early poems, saying, however, that I had managed to invent a

metric!

I

also really enjoyed Larry Rivers’ quirky and minimal interpretation of David Sylvester ('Mr Art'), an

‘outsider’ art critic and curator, who was particularly famous for promoting

the works of Joan Miró, Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon.

|

| ‘Private View of the Old Masters Exhibition, Royal Academy, 1888’ by Henry Jamyn Brooks ©National Portrait Gallery |

|

| Larry Rivers/VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2012 ©National Portrait Gallery |

It was time to go, so we left for Islington, preferring

the bus, which allows you to get a ‘bird’s eye view’ of London. It was bitterly

cold and despite being a Saturday afternoon, the city streets were strangely laid-back

and deserted, thanks to the wintery weather.

On arriving at the bustling and labyrinthine London Art

Fair – and, after brushing quickly past the glitzy Damien Hirst skull prints et al., -

first up, for me at least, was ‘Monotheism’, a spooky interior by Giles Alexander. Exhibited

by The Fine Art Society Contemporary,

the works, which are inspired by quantum physics, have a glossy, almost photographic

quality. The looming spaces, filled with symbolic objects, are gloomy and

blurred; a warped and eerie, possibly parallel reality, as if seen through the

mind’s eye or a crystal ball.

|

| Monotheism by Giles Alexander |

One of the most interesting galleries by

far was Charlie Smith London, directed by Zavier Ellis – a very welcoming and

friendly fellow – and co-founder of THE FUTURE CAN WAIT, who has

curated exhibitions as far afield as Berlin, Helsinki, Klaipeda, London, Los

Angeles, Naples, New York and Rome.

With works ranging from around 2,500 to 30,000 pounds (more or less, the stand

was too crowded to check all of the prices), they present an eclectic and

high-quality selection of works.

I instantly fell in love with John Stark’s weird and

wonderful, almost Boschian-style oil paintings on wooden panels. In the

‘Apiculture’ series, each image leads the viewer on a fascinating and

disturbing journey to an oneiric world. Monk-like, hooded ‘keepers’ tend to

hives full of a mysterious, glowing liquid in a strange, apparently ‘utopian’

universe, still scattered with what seems to be the remains of a lost

civilisation.

The faces of the ‘workers’ are

always hidden or they seem to be engaged in some esoteric and ritualistic activity,

with their backs towards the viewer. They successfully unsettle the viewer,

morbidly drawing you in, urging you to piece together the artist’s unfinished

tale. As you observe, a myriad of questions bubble to the surface: Are they

free or have they been enslaved? And if so, by what?; Has the world been

invaded by an alien race?; Is he referencing the theories of Interventionism?; Are

they guardians of a dying world or the architects of a brave new one?; Are they

lovingly protecting the world’s resources or are they but mere ‘drones’ intent

on exploiting them?; Is Stark referring to humanity and our own hive-like

mentality?... You could go on and on. Looking at his production, the evolution

of his work is not only prolific but also coherent. Worthy of an entire

article, a good critique by artist-curator Juan Bolivar, can be found on the

artist’s website: http://johnstarkgallery.co.uk/news.html.

|

| From the Black Mirror series by John Stark ©Charlie Smith London |

|

| From the Apiculture series by John Stark ©Charlie Smith Londonon |

Another interesting artist on the stand was Tom Ormond with his intriguing and dynamic oil paintings of derelict buildings. These complex, futuristic paintings reveal a fascination for architecture, space-colonisation and war technologies, whilst exploring the dualities of problem solving and failure, utopia and dystopia. In fact, it looks as if the worlds could suddenly implode, fall down like a stack of dominoes, disintergrate, or recompose themselves in one swoop. Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and Paolo Soleri, Ormond also draws inspiration from his visits to a number of locations, such as Biosphere 2, in Tuscon, Arizona and the Trinity test site, in New Mexico, where the first atom bomb was tested, and the imagery of nuclear explosions, clouds of gas, scaffolding and electrical components are all incorporated in his dynamic compositions.

|

| Emma Bennet, ‘Thief of Time |

Then there was Emma Bennet, with ‘Thief of Time’, a delicate still life on a black background.

It is as if somehow the tradition’s of the past are fading, passing us by,

their mark receding and shrinking with the passing of time, like a distant memory.

Her works are reminiscent of Flemish paintings, but here the bounty is reduced,

cut down to size, almost pushed out by the suffocating presence of a dark, foreboding

void.

|

| Bertende (2006) by Caro Suerkemper ceramic h. 46 cm |

Meanwhile, Gavin Nolan’s

juxtaposition of portraiture and modernist-style geometric forms still leaves

me teetering on the edge of indecision, but he’s certainly someone to keep an

eye on.

I could have got lost for hours, as the stand was a real delight

to explore, not only for the combination of good quality work but also the

techniques used by the artists, who have, in my opinion, ably combined the ‘new’

with traditional techniques and mediums. I’m definitely looking forward to

seeing what this gallery comes up with in future.

Long & Ryle also had an array of impressive artists, including Nick Archer, Simon Casson and John Monks (see highlights below).

Moving on, ‘Intertwangleism’ by Butch Anthony is a humorous

series of ‘defiled’ paintings and photographs. And, by the sounds of it, this

American folk artist has grand designs: “Intertwangleism

is how I look at people and break them down to their primordial beginnings.

Almost like x-ray vision, seeing through a person’s clothes, through their

skin, and muscles and veins and bones even their shadow. These first

skeletonised paintings are just the first phase of my theory to take over the

art world as we know it.” [cited from the

article Upcoming event: Butch Anthony’s Interwangelism’ by Chris Wilson,

Société Perrier]. Hmm, we shall see...

The Art Projects area, which showcases

the emerging galleries, was a bit of a disappointment for me, but there were

still some interesting works (I’ll be mentioning some of these in the photo

feature later on).

|

| Beach and Light (2012) by Ernesto Canovas Cortesy: Partrick Davies Contemporary |

I think one of my favourite in this area had to be Patrick Davies Contemporary,

from Hertfordshire, who made what I thought was the rather risky decision of

exhibiting only one artist – not because the work wasn’t valid, but more for

economic reasons... This artist was Ernesto

Canovas, a graduate from the Slade

School of Fine Art, who was shortlisted for The Catlin Guide, in 2010, as one of “the

40 most promising new graduate artists in the UK”.

In the ‘Obscure Truth’

series, Canovas draws from history and popular culture transferring images and

stills from old and new media onto wooden panels, which he then covers in

layers of resin, intervening directly on the image, almost like a laboratory

technician, painting and rubbing out, until parts of the composition almost

vanish. They feel and look like a real labour of love. The process in itself,

struck me as being similar in nature to photographic development, but also

relies on traditional painting techniques and mediums, which can be seen in the beautiful sheen and the rings of the wood that peek through the surface,

begging to be touched. Here the artist plays on our desires and uncertainties:

you have the very palpable sense of something slipping away; the painful impossibility

of definitively crystalising a fading face, voice, or recollection in our minds.

By Sarah Silver

All images are copyright of the respective artists, galleries and photographers.

All images are copyright of the respective artists, galleries and photographers.

More London Art Fair highlights:

|

|

|

Bridging the

Gap (2012) by ThomasWatson – Jill George

Gallery

|

Video by Oliver Michaels – London Art Fair Film Programme

Jesus with wings by Nancy Fout

©Nancy Fout

©Nancy Fout

Anomalous God is Not Great No. 1 by Christina

Mitresntese – Dalla Rosa

Gallery

‘Intertwangleism’ series by Butch Anthony

04:41 Classic Boxing (2012) by Ben

McLaughan – William Stephens Fine Art

.jpg)